Real time Django

Django

When Django was created, over ten years ago, the web was a less complicated place. The majority of web pages were static. Database-backed, Model/View/Controller-style web apps were the new spiffy thing. Ajax was barely starting to be used, and only in narrow contexts.

The web circa 2016 is significantly more powerful. The last few years have seen the rise of the so-called “real-time” web: apps with much higher interaction between clients and servers and peer-to-peer. Apps comprised of many services (a.k.a. microservices) are the norm. And, new web technologies allow web apps to go in directions we could only dream of a decade ago. One of these core technologies are WebSockets: a new protocol that provides full-duplex communication — a persistent, open connection between the client and the server, with either able to send data at any time.

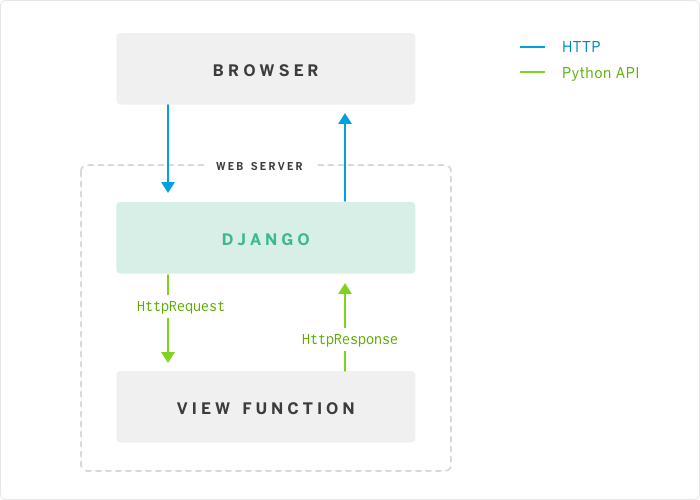

In this new world, Django shows its age. At its core, Django is built around the simple concept of requests and responses: the browser makes a request, Django calls a view, which returns a response that’s sent back to the browser:

This doesn’t work with WebSockets! The view is only around for the lifespan of a single request, and there’s no mechanism to hold open a connection or send data down to the client without an associated request.

Thus: Django Channels. Channels, in a nutshell, replaces the “guts” of Django — the request/response cycle — with messages that are sent across channels. Channels allows Django to support WebSockets in a way that’s very similar to traditional HTTP views. Channels also allow for background tasks that run on the same servers as the rest of Django. HTTP requests continue to behave the same as before, but also get routed over channels. Thus, under Channels Django now looks like this:

As you can see, Channels introduces some new concepts to Django:

Channels are essentially task queues: messages get pushed onto the channel by producers, and then given to one of the consumers listening on that channel. If you’ve used channels in Go, the concept should be fairly familiar. The main difference is that Django channels work across a network and allow producers and consumers to run transparently across many dynos and/or machines. This network layer is called the channel layer. Channels is designed to use Redis as its preferred channel layer, though there is support for other types (and a first-class API for creating custom channel layers). There are neat and subtle technical details; consult the documentation for the full story.

Right now, Channels is available as a stand-alone app that works with Django 1.9. The plan is to roll Channels into Django for the 1.10 release, due out some time this summer.

I believe that Channels will be an incredible important addition to Django: they allow Django to move smoothly into this new age of web development. Although these APIs aren’t part of Django yet, they will be soon! So, now’s a perfect time to start learning about Channels: you can learn about the future of Django before it lands.

Getting started: how to make a real-time chat app in Django

As an example, I’ve built a simple real-time chat app — like a very, very light-weight Slack. There are a bunch of rooms, and everyone in the same room can chat, in real-time, with each other (using WebSockets).

You can visit my deployment of the example online, check out the code on GitHub, or deploy your own copy with this button (which requires a free Heroku account, so sign up for that first):

Note: you'll need to scale the

worker process type up after using the button. Use the Dashboard, or run heroku ps:scale web=1:free worker=1:free.

For in-depth details on how the app works — including why you need

worker dynos! — read on. I’ll walk through the steps to take to build this app, and highlight the import bits and concepts along the way.First steps — it’s still Django

Although there are differences under the hood, this is still the same Django we’ve been using for ten years. So the initial steps are the same as any Django app. (If you’re new to Django, you might want to check out Getting Started With Python on Heroku and/or the Django Girls Tutorial.) After creating a project, we can define model to represent a chat room, and the messages within it (chat/models.py):

class Room(models.Model):

name = models.TextField()

label = models.SlugField(unique=True)

class Message(models.Model):

room = models.ForeignKey(Room, related_name='messages')

handle = models.TextField()

message = models.TextField()

timestamp = models.DateTimeField(default=timezone.now, db_index=True)

(In this, and all subsequent examples, I’ve trimmed the code down to the bare minimum, so we can focus on the important bits. For the full messy detailed code, see the project on Github.)

def chat_room(request, label):

# If the room with the given label doesn't exist, automatically create it

# upon first visit (a la etherpad).

room, created = Room.objects.get_or_create(label=label)

# We want to show the last 50 messages, ordered most-recent-last

messages = reversed(room.messages.order_by('-timestamp')[:50])

return render(request, "chat/room.html", {

'room': room,

'messages': messages,

})

At this point, we have a functioning — if unexciting — Django app. If you run this with a standard Django install, you’d be able to see existing chat rooms and transcripts, but not interact with them in any way. Real-time chat doesn’t work — for that we need something that can handle WebSockets.

Where we’re going

To get a handle on what is needed to be done on the backend, let’s look at the client code. You can find it in chat.js— and there isn’t much of it! First, we create a websocket:

var ws_scheme = window.location.protocol == "https:" ? "wss" : "ws";

var chat_socket = new ReconnectingWebSocket(ws_scheme + '://' + window.location.host + "/chat" + window.location.pathname);

Note that:

- Like HTTP and HTTPS, the WebSocket protocol comes in secure (WSS) and insecure (WS) flavors. We need to make sure to use the “correct” flavor.

- Because Heroku’s router has a 60-second timeout, I use a little shim around the browser WebSocket that automatically reconnects if the socket gets disconnected. (Thanks to Kenneth Reitz, who pointed this out in his Flask WebSocket example.)

Next, we’ll wire up a callback so that when the form’s submitted, we send data over the WebSocket (rather than POSTing it):

$('#chatform').on('submit', function(event) {

var message = {

handle: $('#handle').val(),

message: $('#message').val(),

}

chat_socket.send(JSON.stringify(message));

return false;

});

We can send any text data we’d like over the WebSocket. Like most APIs, JSON is easiest, so we’ll bundle up the data as JSON and send it that way.

Finally, we need to wire up a callback to fire when new data is received on the WebSocket:

chatsock.onmessage = function(message) {

var data = JSON.parse(message.data);

$('#chat').append('<tr>'

+ '<td>' + data.timestamp + '</td>'

+ '<td>' + data.handle + '</td>'

+ '<td>' + data.message + ' </td>'

+ '</tr>');

};

Simple stuff: just append a row to our transcript table, pulling data out of the received message. If I run this code now, it won’t work — there’s nothing listening to WebSocket connections, just HTTP. So now, let’s turn to connecting WebSockets.

Installing and setting up Channels

To “channel-ify” this app, we’ll need to do three things: install Channels, set up a channel layer, define channel routing, and modify our project to run under Channels (rather than WSGI).

1. Install Channels

To install Channels, simply

pip install channels, then add "channels” to your INSTALLED_APPS setting. Installing Channels allows Django to run in “channel mode”, swapping out the request/response cycle with the channel-based architecture described above. (For backwards-compatibility, you can still run Django in WSGI mode, but WebSockets and all the other Channel features won’t work in this backwards-compatible mode.)2. Choose a channel layer

Next, we need to define a channel layer. This is the transport mechanism that Channels uses to pass messages from producers (message senders) to consumers. It’s a type of message queue with some specific properties (see the Channels documentation for details).

We’ll use Redis for our channel layer: it’s the preferred production-quality channel layer, and the obvious choice when deploying to Heroku. There are also in-memory and database-backed channels layers, but those are more suited to local development or low-traffic usage. (For more details, again refer to the documentation.)

But first: because the Redis channel layer is implemented in a different package, we’ll need to

pip install asgi_redis. (I’ll talk a bit more about what “ASGI” is below.) Then, we define our channel layer in the CHANNEL_LAYERS setting:CHANNEL_LAYERS = {

"default": {

"BACKEND": "asgi_redis.RedisChannelLayer",

"CONFIG": {

"hosts": [os.environ.get('REDIS_URL', 'redis://localhost:6379')],

},

"ROUTING": "chat.routing.channel_routing",

},

}

Note that we’re pulling the Redis connection URL out of the environ, to future-proof for when we eventually deploy to Heroku.

3. Channel routing

In

CHANNEL_LAYERS, we’ve told Channel where to look for our channel routing — chat.routing.channel_routing. Channel routing is a very similar concept to URL routing: URL routing maps URLs to view functions; channel routing maps channels to consumer functions. Also similar to urls.py, by convention channel routes live in a routing.py. For now, we’ll just create an empty one:channel_routing = {}

(We’ll see a few channel routes below, when we wire up WebSockets.)

You’ll notice that our example app has both a

urls.py and a routing.py: we’re using the same app to handle HTTP requests and WebSockets. This is expected, and typical: Channels apps are still Django apps, so all the features you except from Django — views, forms, models, etc. — continue to work as they did pre-Channels.4. Run with channels

Finally, we need to swap out Django's HTTP/WSGI-based request handler, for the one built into channels. This is based around an emerging standard called ASGI (Asynchronous Server Gateway Interface), so we’ll define that handler in an

asgi.py file:import os

import channels.asgi

os.environ.setdefault("DJANGO_SETTINGS_MODULE", "chat.settings")

channel_layer = channels.asgi.get_channel_layer()

(In the future, Django will probably auto-generate this file, like it currently does for

wsgi.py.)

At this point, if we got everything right, we should be able to run the app under channels. The Channels interface server is called Daphne, and we can run our app with it like so:

$ daphne chat.asgi:channel_layer --port 8888

** If we now visit

http://localhost:8888/ we should see…. nothing happen. This might be confusing, until you remember that Channels splits Django into two parts: the front-end interface server, Daphne, and the backend message consumers. So to actually handle HTTP requests, we need to run a worker:$ python manage.py runworker

Now, requests should go through. This illustrates something pretty neat: Channels continues to handle HTTP(S) requests just fine, but it does it in a complete different way. this isn’t too different from running Celery with Django, where you’d run a Celery worker alongside a WSGI server. Now, though, all tasks — HTTP requests, WebSockets, background tasks — get run in the worker.

(By the way, we can still run

python manage.py runserver for easy local testing. When we do, Channels simply runs Daphne and a worker in the same process.)WebSocket consumers

All right, enough setup; let’s get to the good parts.

Channels maps WebSocket connections to three channels:

- A message is sent to the

websocket.connectchannels the first time a new client (i.e. browser) connects via a WebSocket. When this happens, we’ll record that the client is now “in” a given chat room. - Each message the client sends on the socket gets sent across the

websocket.receivechannel. (These are just messages received from the browser; remember that channels are one-direction. We’ll see how to send messages back to the client in a bit.) When a message is received, we’ll broadcast that message to all the other clients in the "room”. - Finally, when the client disconnects, a message is sent to

websocket.disconnect. When that happens, we’ll remove the client from the “room”.

First, we need to hook each of these channels up in

routing.py:from . import consumers

channel_routing = {

'websocket.connect': consumers.ws_connect,

'websocket.receive': consumers.ws_receive,

'websocket.disconnect': consumers.ws_disconnect,

}

Pretty simple stuff: just connect each channel to an appropriate function. Now, let’s look at those functions. By convention we’ll put these functions in a

consumers.py (but, like views, these could be anywhere.)

Let’s look at

ws_connect first:from channels import Group

from channels.sessions import channel_session

from .models import Room

@channel_session

def ws_connect(message):

prefix, label = message['path'].strip('/').split('/')

room = Room.objects.get(label=label)

Group('chat-' + label).add(message.reply_channel)

message.channel_session['room'] = room.label

(For clarity, I’ve stripped all the error handling and logging from this code. To see the full version, see consumers.pyon GitHub).

This is dense; let’s go line-by-line:

7. The client will connect to a WebSocket with a URL of the form

/chat/{label}/, where label maps to a Room’s label attribute. Since all WebSocket messages (regardless of URL) get sent to the same set of channel consumers, we’ll need to work out which Room we’re talking about by parsing the message path.

Notice that the consumer is responsible for parsing the WebSocket path by reading

message['path'] . This is different from traditional URL routing, where Django’s urls.py routes based on path; If you have multiple WebSocket URLs, you’ll need to route to different functions yourself. (This is one place where the “early-days” aspects of Channels shows; it’s quite likely that future versions of Channels will include WebSocket URL routing.)

8. Now, we can look up the

Room object from the database.

9. This line’s the key to making chatting work. We need to know how to send messages back to this client. For that, we’ll use the message’s

reply_channel — every message will have a reply_channel attribute, which we can use to send messages back to the client. (We don’t need to create that channel ourselves; Channels creates it for us.)

However, it’s not going to be good enough to just send messages to that one channel; when a user chats, we want to send messages to everyone who's connected to that room. For that, we’ll use a channel group. A group is simply a connection of channels that you can broadcast messages to. So, we’ll add this message’s

reply_channel to a group specific to this chat room.

10. Finally, subsequent messages (receive/disconnect) won’t contain the URL anymore (since the connection is already active). So, we need a way of “remembering” which room a WebSocket connection maps to. For this, we can use a channel session. Channel sessions are very similar to Django's session framework: they persist data between channel messages on an attribute called

message.channel_session. Adding the @channel_sessiondecorator to a consumer is all we need to make sessions work. (The documentation has more details on how channel sessions work).

Now that a client is connected, let’s take a look at

ws_receive. This consumer will get called each time a message is received on the WebSocket:@channel_session

def ws_receive(message):

label = message.channel_session['room']

room = Room.objects.get(label=label)

data = json.loads(message['text'])

m = room.messages.create(handle=data['handle'], message=data['message'])

Group('chat-'+label).send({'text': json.dumps(m.as_dict())})

(Once again, I’ve stripped error handling and logging for clarity.)

The first few few lines are pretty simple: extract the room from the

channel_session, look it up in the database, parse the JSON message, and store the message in the database as a Message object. After that, all we have to do is broadcast this new message to everyone in the chat room, and for this we’ll use the same channel group as before. Group.send() will take care of sending this message to every reply_channel added to the group.

After that,

ws_disconnect is very simple:@channel_session

def ws_disconnect(message):

label = message.channel_session['room']

Group('chat-'+label).discard(message.reply_channel)

Here, after looking up the room in the channel session, we disconnect (

discard) the reply_channel from the chat group. That’s it!Deploying and scaling

Now that we’ve got WebSockets hooked up and working, we can test it out by running

daphne and runworker, as above (or by running manage.py runserver). But it’s lonely talking to yourself, so let’s see what it takes to get this running on Heroku!

For the most part, a Channels app works the same as an Python app as Heroku — specify requirements in

requirements.txt, define a Python runtime in runtime.txt, deploy with the standard git push heroku master, etc. (For a refresher, see the Getting Started with Python on Heroku tutorial.) I’ll just highlight the differences between a Channels app and a standard Django app:1. Procfile and process types

Because Channels apps need both a HTTP/WebSocket server and a backend channel consumer, the

Procfileneeds to define both of these types. Here’s our Procfile:web: daphne chat.asgi:channel_layer --port $PORT --bind 0.0.0.0 -v2

worker: python manage.py runworker -v2

And, when we do our initial deploy, we’ll need to make sure both process types are running (Heroku will only start the

web dyno by default):$ heroku ps:scale web=1:free worker=1:free

(A simple app will run within the limits of Heroku’s free or hobby tiers, though for real-world usage you’ll probably want to upgrade to production dynos to handle better throughput.)

2. Addons: Postgres and Redis

Like most Django apps, you’ll want a database, and Heroku Postgres is perfect for that. However, Channels also requires a Redis instance to act as the channel layer. So, we’ll want to create both a Heroku Postgres and a Heroku Redis instance when deploying our app for the first time:

$ heroku addons:create heroku-postgresql

$ heroku addons:create heroku-redis

3. Scaling

Since Channels is fairly new, the scalability issues aren’t quite known yet. However, I can make a few guesses based on the architecture and some early performance tests I ran. The key is that Channels splits processes between those responsible for handling connections (

daphne), and those responsible for handling channel messages (runworker). This means that:- The throughput of channels — HTTP requests, WebSocket messages, or custom channel messages — is mostly determined by the number of worker dynos. So, if you need to handle greater request volume, you’ll do it by scaling up worker dynos (e.g.

heroku ps:scale worker=3). - The level of concurrency — the number of current open connections — will mostly be limited by the scale of the front-end web dyno. So, if you needed to handle more concurrent WebSocket connections, you’d scale up the web dyno (e.g.

heroku ps:scale worker=2)

Based on my early performance tests, Daphne is quite capable of handling many hundreds of concurrent connections on a Standard-1X dyno, so I expect it’ll be rare to have to scale up the web dynos. The number of worker dynos in a Channels app seems to map fairly closely to the number of needed web dynos in a similar old-style Django app.

What’s next?

WebSocket support is a huge new feature for Django, but it only scratches the surface of what Channels can do. Remember: Channels is a general-purpose utility for running background tasks. Thus, many features that used to require Celery or Python-RQ could be done using Channels instead. Channels can’t replace dedicated task queues entirely: it has some important limitations, including at-most-once delivery, that don’t make it suitable for all use cases. See the documentation for full details. Still, Channels can make common background tasks much simpler. For example, you could easily use Channels to perform image thumbnailing, send out emails, tweets, or SMSes, run expensive data calculations, and more.

As for the Channels itself: plan is to include Channels in Django 1.10, which is scheduled for release this summer. This means that now’s a great time to try it out and give feedback: your input could help drive the direction of this critical feature. If you want to get involved, check out the guide to Contributing to Django, then hop onto the django-developers mailing list to share your feedback.

Comments

Post a Comment